“I now understand that trauma derives a lot of its power from the shame we layer upon it.

The doctor held my penis in his right hand for my parents to see.

I was 7 and lying on the examination table at my pediatricians office.

My right testicle was the focus.

It had made a home within my groin.

But occasionally a child is born with one or both testicles undescended.

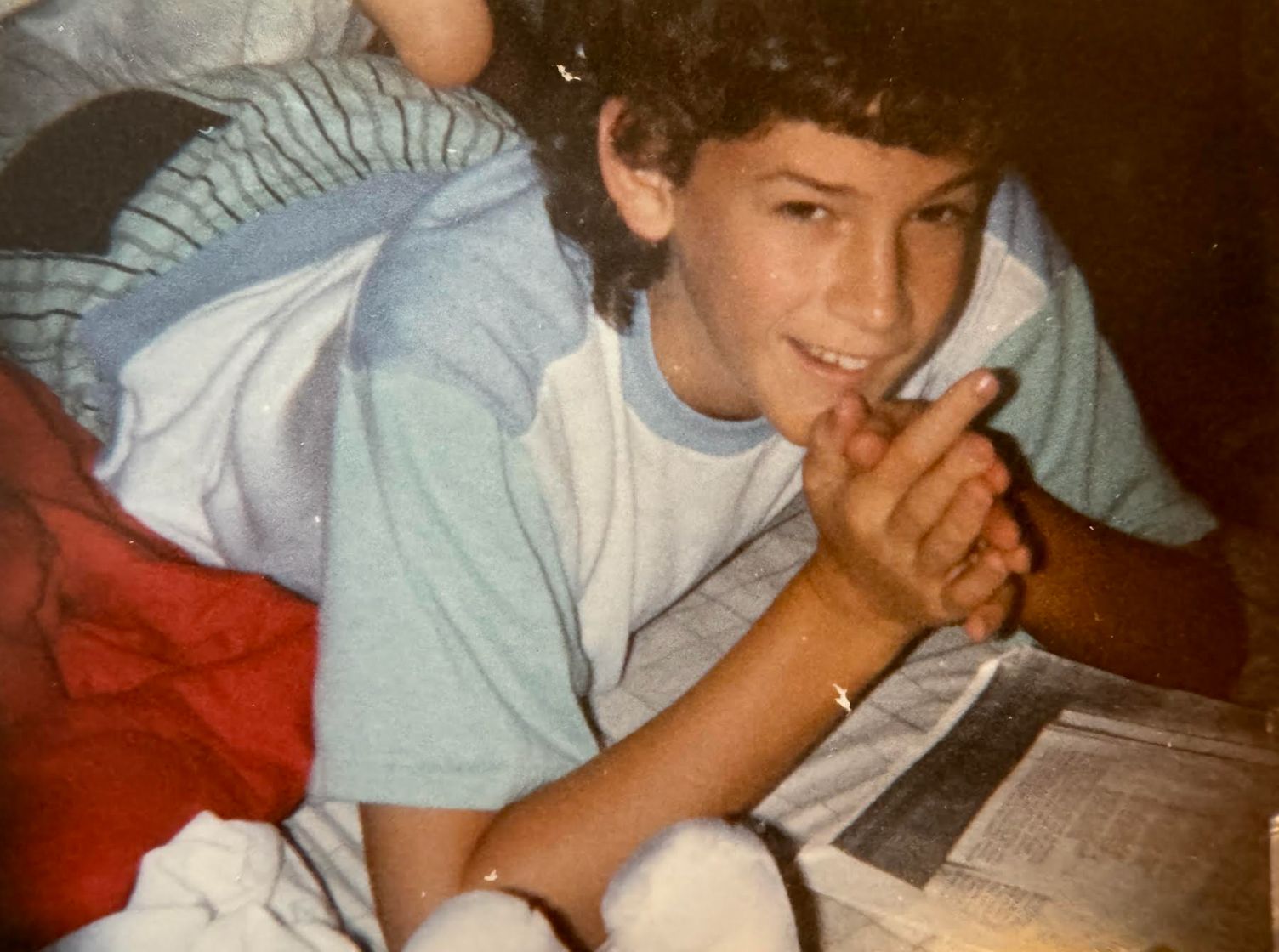

It was the early 80s.

I wanted to scream.

I wanted to run away.

I wanted to be anywhere but that office.

Before puberty, he explained, a testicle can sometimes ascend back into the groin spontaneously.

Or it can end up there as a result of force.

The word force immediately brought to mind a street hockey game from months earlier.

One of the bigger kids, Paul, hit a slap shot that landed in my nuts.

I could kill Paul.

His words sent waves of terror crashing along every shore of my body.

Tears streamed down my face.

The name for this condition, when originating at birth, is cryptorchidism.

It derives from theGreek wordskryptosandorchis, meaning hidden and testicle.

Data suggests that2% to 8% of newbornsexperience it.

An additional incision is made in the scrotum to create a pocket.

Then, using a grasping tool, the doctor gently pulls the undescended testicle down into the pocket.

The surgery has a high success rate.

Doctors note that it typicallyimproves a childs self-esteem by reducing future embarrassment.

After Dr. R terrified and humiliated me, he kept me on the examination table.

He used his right hand to locate the outer shell of my wayward testicle.

The pressure made me nauseated.

hey stop, I said.

The doctor continued kneading my testicle like a baker manipulating dough.

Just a little longer, he said.

As I pushed harder to get off the table, my father helped hold me down.

It was all so primitive the hands of men and their force.

The doctor continued pressing until I felt my testicle pop into my scrotum.

I cried tears of relief.

I told the doctor what Id felt.

We can give it another spin another time, the doctor said.

TheMayo Clinic reportsthat having a testicle outside the scrotum increases the risk of testicular cancer and infertility.

I learned about these health risks when I overheard Dr. R whispering to my parents.

I prayed that I wouldnt get cancer.

I prayed that no one else in the world would ever find out.

The teacher passed around a synthetic model of a scrotum.

It contained a pebble-like lump for us to discover so wed know what a testicular tumor felt like.

I held the model, imagined my future tumor and ran from the room to vomit.

When the absurdity of that conclusion sunk in, I resorted to more scientific but no less wishful thinking.

Those tries also left me in tears.

By age 13, Dr. R told me hed make one last try before surgery became necessary.

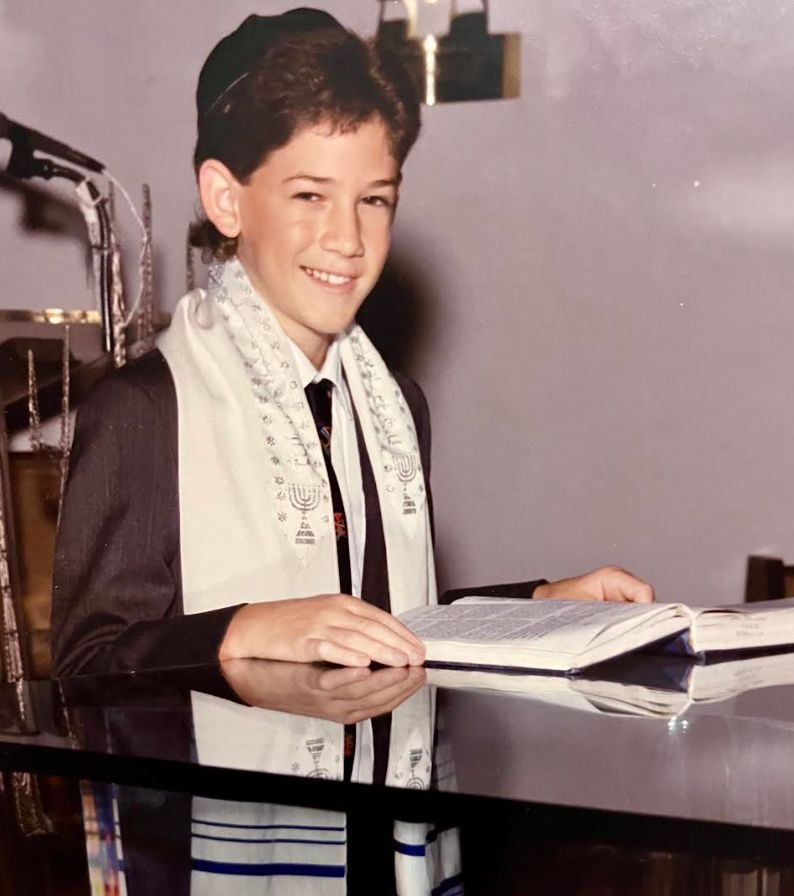

The appointment was scheduled for a week before my bar mitzvah.

The timing felt like an ominous coincidence or the opportunity for a miracle.

I continued to practice my Torah reading for a ceremony that would mark my passage into manhood.

It was a continuation of years of silence.

My parents lacked the language to speak with me about what was happening.

Everyone was too focused on fixing the physical aspects of my condition to notice my emotional wounds.

I kept my shame and my fear to myself.

Once in the examination room, it was another high-tech affair.

while Dr. R crept up behind me like a Scooby-Doo villain.

Again, he used his right hand to apply pressure on the outer rim of my right testicle.

Again, it made me instantly nauseated.

Again, I was crying.

But this time, with every centimeter of testicular travel, Dr. R was becoming my hero.

I stood as still as a statue.

I would have stood there forever if it meant avoiding an operating room.

I wanted this testicle to be inside my scrotum more than anything in the world.

There, Dr. R said.

The eagle had landed.

The testicle didnt pop back up.

It felt like it belonged there.

My entire body exhaled.

I could have floated to the ceiling.

One week from my bar mitzvah, I was a new man.

If there were anything that could prove Gods existence, this was it.

Dr. R was thinking in less celestial terms.

have a go at avoid getting hit there, he said.

Trauma is a stubborn thing.

It doesnt just disappear.

After Dr. Rs success in descending my testicle, I lived in fear of it happening again.

My jumpiness elicited discomfort in others who lacked context for my behavior.

Confiding about my childhood experience to anyone else was unthinkable it remained a dark secret.

I avoided swimming pools after noticing that cool water pushed my right testicle upward.

Doctor visits still stirred the same dread.

I fixated on the slightest discomfort in my groin.

Time, the saying goes, heals all wounds.

This turns out not to be true.

Sure, time can provide the chance for physical recovery, but Ive learned that healing requires something more.

In my mid-20s, I finally found the courage to share my secret with a boyfriend.

One evening, while we touched, I broke through the silence Id perfected for years.

I had an injury down there, I said.

Oh, he replied.

What kind of injury?

I am so sorry you had to go through that, my boyfriend said.

I promise to be gentle.

Thirty years after Dr. Rs discovery, my childhood shame and fear remain a part of me.

Instead, I find myself drawing from the experience.

I now understand that trauma derives a lot of its power from the shame we layer upon it.

I know about the corrosive effects of secrecy.

I had once held a different kind of secret about my sexuality from family and friends.

I was fortunate to be met with affirmation each time I confided in others.

But I amplified my unease for years by keeping my truth a secret.

Im now a husband and a father of two children, an 11-year-old girl and a 2-year-old boy.

I am attuned to their inner lives in ways I trace to my childhood nights.

With my eldest, Ive learned that Whats on your mind?

is often a better question than How are you doing?

These are small examples of doing what I wish had been done for me.

Im mindful of how easy it is to link our self-worth to the experience of our bodies.

Ive also absorbed the lesson that many of the experiences that shape us most can be invisible to others.

We dont always see the heavy things people are carrying.

But knowing that everyone hassomethingtransforms the way one moves through the world.

It nudges us toward compassion.

To be sure, Ive gleaned lighter lessons, too.

For starters, if my son plays street hockey, he will wear a cup.

And despite my skepticism of a higher being, it certainly doesnt hurt to pray.

Finally, Ive learned that wounds can remain long after they stop hurting.

Sometimes its the scars that help us remember whats important.

He is pursuing his masters in creative nonfiction writing at Bay Path University.

it’s possible for you to find more of his work atbradmsnyder.comand onMedium.

This post originally appeared onHuffPost.